Cincinnati businessman David Parlin was supposed to be invested in Treasury STRIPS. Instead he was stripped of $4 million — and most of his dignity — by Philadelphia Pastor Tyron L. Gilliams, Jr. The Pastor is also a hip-hop music promoter and a self-produced reality TV personality. On the side, he pretends he’s running a global commodities trading firm. With Gilliams now convicted on a federal indictment, and facing an SEC complaint and a civil action by investors, now is a good time to take a closer look at what we in the investment world call “Red Flags.”

Spotting a Red Flag in the Wild

Red flags are clues suggesting that an investment opportunity is a scam. Some red flags are obvious, while others appear only upon further inquiry by an investor. Identifying red flags after an investment is exposed as a scam is easy (we’ll be doing that today). Doing it beforehand is the trick. By far the best example of doing it beforehand is derivatives expert Harry M. Markopolos’s 2005 letter to the SEC asserting that Bernard Madoff was running a massive Ponzi scheme. The letter, with its arresting title, “The World’s Largest Hedge Fund is a Fraud,” is nineteen single-spaced pages long and it describes twenty-nine red flags. If you have never seen this document, which Markopolos sent to the SEC years before the Madoff fraud was finally exposed by Madoff himself, it is a must read (well, okay, it’s a must skim for those unlettered in options trading). As we now know, the piece fell through the cracks at the SEC. But back to Gilliams.

Gilliams’s Treasury STRIPS Program

Before we Monday-morning quarterback the red flags in this case, let’s sketch out the basic facts, which we got from the indictment, the SEC Complaint, and from some excellent reporting by Reuter’s Matthew Goldstein (found here, here, and here) and from his terrific video report on the story, which features Goldstein’s smiling commentary from his desk in the middle of a Dilbert-style cubicle farm at Reuters.

![]() David Parlin made his fortune running a company that refurbished ATM machines. He later created a foundation for investment purposes, the director of which was one Vassilis Morfopoulos, a 73-year-old New York financier, who was given authority to direct some foundation investments. Through some acquaintances, Morfopoulous learned that Gilliams operated a lucrative “Treasury STRIPS trading program.”

David Parlin made his fortune running a company that refurbished ATM machines. He later created a foundation for investment purposes, the director of which was one Vassilis Morfopoulos, a 73-year-old New York financier, who was given authority to direct some foundation investments. Through some acquaintances, Morfopoulous learned that Gilliams operated a lucrative “Treasury STRIPS trading program.”

For those of you skilled at avoiding dull subjects, STRIPS is an acronym: “Separate Trading of Registered Interest and Principal of Securities.” A Treasury STRIP is born in the hands of a broker-dealer, who takes interest-paying government securities (Treasury Notes, Treasury Bonds, and Treasury Inflation Protected Securities) and separates (“strips”) away each of the future interest payments and sells each of them as a separate zero-coupon bond in the secondary market. Some outfit named “Bionic Turtle” explains how they work in this video, which will bring back bad memories for anyone who’s had to sit through student presentations in business school.

Anyway, Morfopoulous learns through others that Gilliams has a profitable program for trading in STRIPS. Morfopoulous wires $4 million of the Parlin foundation’s funds to participate in the program. In trust law, we’d call this an “imprudent” investment decision, as you will later see. Morfopoulous is now being sued by the Parlin foundation. Could Morfopoulous possibly have missed some “red flags” along the way, or shortly after investing?

Hey, is That a Red Flag?

Not all red flags are equal. On one hand, you have the obvious red flags. For example, if someone promises you a 43% return on investment every three months with the principal “guaranteed,” that is a red flag. Guaranteed investments don’t need to offer anything near 43% per quarter to attract investors, so why would they? They wouldn’t. On the other hand, some red flags appear through minimal further inquiry. For example, if someone wearing $5,000 Cowboy Boots offers to sell you unregistered debentures claiming that they are “backed” by coal deposits “valued at $11.8 billion,” some further inquiry is warranted; namely, what coal mines? who owns them? who valued them? what documents provide for the backing? and why are you wearing $5,000 Cowboy Boots?

So, on to the red flags.

(1) “Gilliams claimed his trading program would yield weekly returns of five per-cent and was virtually risk-free.”

“Virtually risk free” is almost aways a red flag, but combined with 5% per week it’s definitely a red flag. Five-percent per week is 1,164% per year. So a $1,000 investment with the Pastor would return a stunning $11,640 in one year plus the $1,000 return of principal. To put this into perspective, a $1,000 investment in a genuine “virtually risk free” investment, U.S. treasury bills, would have returned — get this — one dollar and 3o cents (the annual rate on one-year treasury bills averaged a whopping .13% in 2010). The Pastor was offering an annual rate 8,953 times higher than treasury bills, with the same risk. That should suffice to raise the eyebrow of anyone qualified to run money for a foundation, no? Only Mr. Scammell’s alleged insider trading returns of 3,500% per month top this.

(2) Gilliams claimed he ran a global commodities trading firm.

Ordinarily it is a relatively good sign that someone you’ve invested with runs a global commodities trading firm — but only if you can verify it. An easy place to start, since you can do it from your couch, is the firm’s website. Here it is, in all its sparkly glory. The “About us” section begins with a brief biographical sketch of Gilliams, Sr., the father, who apparently (the details are vague) worked his way up the ranks in the oil industry. It concludes with this impressive assertion:

[Gilliams Sr.’s] contacts and relationships with the world’s leading oil companies such as Exxon Mobil, Shell & BP, and his connectivity to the ministers of industry and government allowed for him to develop a platform for the procurement of crude as a primary product for use and sale.

Nothing further is explained about the relationships or this “connectivity.” The author clearly wants to drop names, but the best he can muster is a suggestion that Dad is connected to names that are worthy of dropping. And as far as achievements go, developing “a platform for the procurement of crude as a primary product for use and sale” is about as impressive as saying: “He bought oil, on credit.” Is this a red flag? I think so, but hindsight is 20-20. Let’s dig deeper.

Next we are told that Gilliams Jr. attended “one of the most prestigious Ivy League schools, the University of Pennsylvania,” where he “achieved star status in academia & sports.” Not a bad start, but then we go right off the deep end:

Tyrone later began a highly profitable business in artist and concert promotions. Due to the extreme success of Tyrone’s concert promotions as a student athlete; he was able to purchase new car(s), fine clothing, jewelry, and cellular phones. This as one would imagine resulted in a closer observation by the NCAA. Albeit, he was viewed by some to have gotten help from the Alum, it amounted to a student athlete conducting prudent business practices forthwith receiving awards.

I have quoted this passage exactly as written, with its interesting grammar and punctuation. Putting aside that this hardly seems the work of one who achieved “star status” in Ivy-League “academia,” there is a bizarrely defensive tone here. Reading between the lines, I see this: In school, Tyrone was flaunting his wealth, including his multiple “cellular phones,” jewelry, and his ambiguously plural “car(s),” and some folks (the NCAA?) suspected he’d received cash from the school, but they were wrong; he was just a great businessman. My translation may be off, but in any event, this peculiar passage does not suggest that we have a phenomenal global commodities trader here. That must come later in the website.

It doesn’t. He goes on to explain, in equally strange prose, that he and “Hip Hop mogul, Sean (Puffy) Combs” entered into a “successful corporate partnership” managing athletes and entertainers. This celebrity endeavor ended 15 years ago, however, and it ended for some rather mysterious reasons. As the website recounts:

Tyrone and Puff formed Bad Boy Sportz which utilized their influence and high profile friends to sign athletes. Unfortunately, due to the East Coast/West Coast battle on and off CD’s/records, resulted in the unfortunate deaths of Tupac Shakur and The Notorious BIG leading to the retirement of Bad Boy Sportz.

That’s an interesting (if oddly worded) story, and Gilliams appears well-connected, but I’m here at the website looking for support that Gilliams can manage investment funds. This passage ain’t doing it.

The “About us” page finally broaches the subject of commodities in the last two paragraphs. There, we are told that in March of 2000, “TL Gilliams, LLC was birthed and to date remains in good standing.” I suppose that’s a relief to know, but it smacks of a rebuttal to unmentioned accusations that it is not. Finally, we get down to the core business:

The primary focus of the business is the trading of commodities (oil, gold, diamonds, sugar, coffee . . . etc.) The long term goal is to build mobile refineries both domestically and internationally. TL Gilliams, LLC has since purchased majority ownership in companies that can help it achieve its goals as it continues to stay above and beyond the learning curve.

There is no further discussion of the company’s business activities. None of the companies he controls are identified. Nothing explains how Gilliams is qualified to build mobile refineries or to trade five different commodities (here’s a quick way to get creamed by commodities professionals — try to simultaneously trade oil, gold, diamonds, sugar, coffee and “etc.”). There is no mention of any STRIPS trading program.

The final paragraph notes that Gilliams “relies on his staff or ‘team’ as he would rather refer to them” to “examine and scrutinize unfamiliar companies that wish to do business with TLG.” So Gilliams is a delegator, is he? Fair enough. Then follows a roll call of his “staff,” as he calls them, just before he calls them his “team.” We learn the firm has a Chief Operating Officer, Chief Financial Officer, an in-house counsel, and an “Internal Analyst.” But none of these esteemed company scrutinizers is identified. Unidentified officers in a global commodities trading firm is a red flag.

The final paragraph, headed “Expansion,” provides no further comfort:

In 2010, further expanding its reach; T.L. Gilliams, LLC has facilitated talks between Nigeria, and Ghana concerning energy and the movement of product. Additionally, this coming year will bring TLG into ownership of a major refinery in Brazil and partial ownership of an already successful trucking company.

That’s it for the business activities. Any questions? Ready to write a check?

There are only two other pages on this entire website. There is a “contact us” page, but it simply displays an email address. There’s no phone number or address (and even more alarming these days, there’s no “follow us on twitter” or “like us on Facebook”).

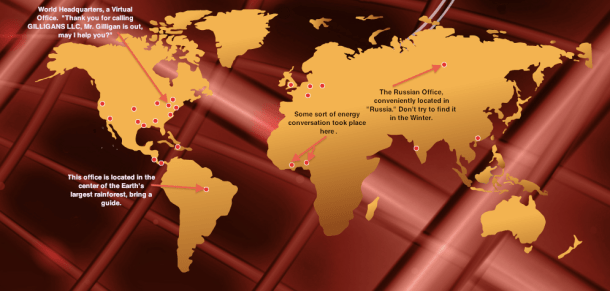

The third and final page is my favorite: “Locations.” There, one finds an impressive golden map of the Earth’s continents with 24 red dots scattered around in North America, Central America, the Caribbean, South America, Europe, Africa, India, China, and Russia. Whew! Clicking the dots does nothing but bring up a city name, or in some cases, only the name of an entire country. It would be difficult indeed to find the office in “Russia” or “Brazil” given that those two words constitute the entire amount of information provided on these locations. This map is more than just a red flag, it’s a caricature of a red flag.

As it turns out, even his “official headquarters” in Philadelphia is illegitimate. As Matthew Goldstein reports:

The official headquarters for his TL Gilliams LLC trading firm, which claims to have offices in two dozen locations around the globe, is a so-called virtual office located in a building in a Philadelphia suburb. Mail is collected for Gilliams at the location and a receptionist takes phone messages. But a person familiar with the facility says the trader rarely shows up in person.

Perhaps he trades oil, gold, diamonds, sugar, coffee and “etc.” on his iPhone. There must be an app for that, right?

Gilliams’s “Locations” Map – With Our Annotations (click for larger view)

This exhausts our mining of the website for anything that would support a decision to wire $4 million to this man. We came up empty. Websites of supposedly successful international financial firms that are short on any detail, vague on all claims, and poorly written are huge red flags. Sorry Morfopoulous, but it is so.

(3) TL Gilliams, LLC was not registered with FINRA or the National Futures Association.

Lack of registration is almost certainly a red flag if a company accepts investor funds for investment in commodities and STRIPS. In many fraudulent cases, the alleged fraud artist is at least somehow affiliated with a registered financial firm. Neither Gilliams nor his firm appear registered in any capacity. Big red flag.

(4) Gillians did not provide legitimate documentation for any STRIPS trades.

Gilliams received $4 million from Morfopoulous and $1 million from another investor for investment in the STRIPS program. As evidence that the funds were so invested, Gilliams created “a screenshot from Bloomberg Finance showing $1 million worth of U.S. Treasury STRIPS, which Gilliams represented was proof that he had purchased Treasury STRIPS.” A screenshot? He must have been in the virtual office that day. A screen shot is not a confirmation. And nobody investing foundation funds should think it is. He also “generated a document, which he supplied to a representative of the investors, in which he purported to show a series of $5 million trades, as well as over $100,000 in purported profits on trades during September and October 2010, [but] this document was false.” Anyone can generate a professional looking document on their computer. I created this fake trade confirmation in 7 minutes. How’d I do? Home-made looking documents that are not from recognized financial firms are red flags.

(5) Gilliams lived like an ultra-rich reality TV star.

Gilliams lives an extravagant lifestyle, much of which is depicted in videos filmed by videographers he hired to follow him around. The videos appear on “TLG TV,” which purports to be some sort of reality TV show starring him. A host of such videos still remain on YouTube, although some were deleted from Vimeo. One such video apparently depicted Gillaims “posing with stacks of money on his lap.”

There is no question that Gilliams is well-connected in certain circles. For example, he sponsored the 2010 Joy to the World Fest, a charity event, complete with a black-tie celebrity gala held at the Ritz Carlton in Philadelphia, which was hosted by his old friend Sean (Puffy) Combs. Videos of the event are on Youtube. He seems to be a skilled event promoter, but this does not a commodities trader make. It’s clear that by entering the world of investing and commodities, Gilliams had strayed far from his core area of competency. Morfopoulous probably should have noticed this.

Morfopoulous probably also should have insisted on knowing where the foundation’s funds were going. Most of the funds never actually saw a STRIPS program, but rather Gilliam blew them on his luxurious lifestyle. Matthew Goldstein reports that one of Gilliams’s videographers has footage of Gilliams blowing $70,000 on drinks. The remainder of the investor funds went to some peculiar places:

- $300,000 to purchase and renovate a medicinal marijuana farm and dispensary;

- $250,000 to a company handling Gilliams’s investment in an Ohio hotel;

- $1,620,080 to Crown Financial Solutions in Ghana for a gold investment in Africa;

- $325,000 to a law firm in Utah for payment on some prior transaction;

- $10,000 to someone who introduced him to a colleague of Morfopoulous;

- $415,000 on personal and unrelated business expenses;

- $450,000 to a private investment company;

- $40,000 to an attorney;

- $20,000 to another person for an introduction;

- $70,000 to the Ritz Carlton for JoyFest;

- $700,000 for other JoyFest-related expenses;

- $303,000 in checks to third parties;

- He spent the rest on hotels, night clubs, airfare, designer apparel, luxury car rental, car payments, and private tuition for his children.

Not knowing exactly where your funds are held is a red flag. In this case, of course, finding out where the funds went would have been a whopping red flag. For his part, Morfopoulous claims that he too was duped by Gilliams, and has pledged to work with Parlin to recover his $4 million. That Morfopoulous was duped is a very tough sell. If the basic alleged facts are correct (they may not be of course), Morfopoulous would have a fiduciary duty to exercise prudence in the investment of foundation funds. Regardless of whether or not he dealt directly with Gilliams or through third parties affiliated with Gilliams, he seems to have violated this charge by ignoring many red flags surrounding what was, at the very least, a highly unusual investment opportunity. But I am Monday-morning quarterbacking here. We’ll watch the case and see how it shakes out. Meanwhile, keep an eye out for red flags. They are everywhere these days.

For an excellent, in-depth review of the Gilliams matter, see Tyrone Gilliams: Ivy League Scam Artist by investigative journalist Stephen Fried.

Update: October 31, 2013, Tyrone Gilliams was sentenced to 10 years in federal prison.

Published by Jeremy L. Bartell

Financially Regulated is published by Jeremy L. Bartell, a long-time admirer of Wall Street and its interesting cast of regulators. Jeremy is an attorney with Bartell Law in Washington D.C. He represents financial professionals nationwide in Finra inquiries and investigations, Finra arbitration, securities employment disputes and registration and disclosure matters.

Financially Regulated is published by Jeremy L. Bartell, a long-time admirer of Wall Street and its interesting cast of regulators. Jeremy is an attorney with Bartell Law in Washington D.C. He represents financial professionals nationwide in Finra inquiries and investigations, Finra arbitration, securities employment disputes and registration and disclosure matters.

What do you think?